In addition to the development of Troy Town, Jacob Cazeneuve Troy had a range of business interests.

His great-grandfather, John Cazeneuve, described himself as a distiller, and this was the occupation Jacob Cazeneuve Troy took up.

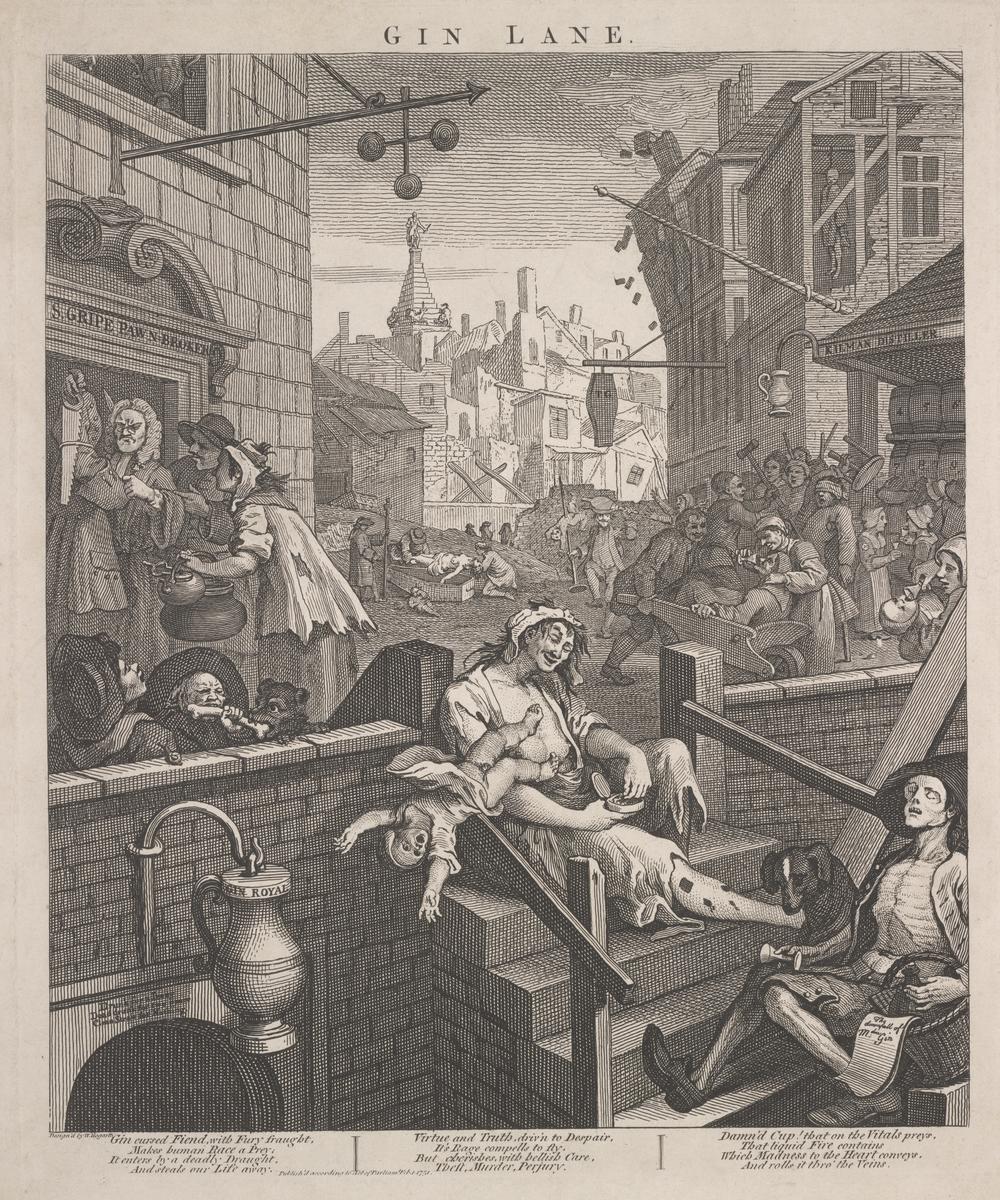

In the eighteenth century, distilling would normally be taken to mean the production of gin. Gin originated in the Netherlands. The name was short for 'geneva', from the juniper berries from which it was made. Gin was so widely consumed in England in the eighteenth century that it was a social problem. In the 1740s it was estimated that over six gallons of gin per person was consumed every year. 'Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for twopence' was the saying.

Gin Lane

William Hogarth, 1751

[Tate Gallery]

Between 1729 and 1751 a series of pieces of legislation known as the 'Gin Acts' attempted to reduce the consumption of gin by imposing duties (to increase the price) and other restrictions on the manufacture and sale of gin. The Gin Acts did have some impact on the legitimate manufacture and sale of gin, but illicit trade continued. As well as back street distilling, the middle decades of the eighteenth century were the great age of smuggling, when large quantities of gin and other spirits were illegally imported and sold.

Jacob Cazeneuve Troy, however, in continuing the family business, no doubt had a respectable trade serving the well to do tradesmen, gentlemen and Naval officers of Chatham and its neighbourhood.

The King's Field, on which Troy Town was built, had been a brickfield. Possibly Jacob's own bricks were used to build some of the houses.

Maidstone Road brickwork

Jacob Cazeneuve Troy was an agent for the Sun Fire Office, an insurance company. He took over the agency in 1780 from his late father in law, Richard Cooke. The company was founded in 1709 and by the 1790s dominated the English insurance market. It had more than 120 agents around England.

Jacob had no shortage of potential customers for his insurance policies; his neighbours in Chatham, the builders and occupiers of the houses in Troy Town, the occupiers of his own estates. Some or all of those purchased policies.

As trade expanded, methods were needed to transfer large sums of money from place to place, both within Britain and overseas. In the late 1730s, Isaac Minet of Dover sent several hundred pounds in gold at a time by the carrier to his family's London office. It was to meet this sort of need that provincial banks developed, usually as a sideline of some already established business. The bankers issued paper notes which could be exchanged at banks in other parts of the country.

By 1750, there were probably more than a dozen banks outside London. By 1784, there were about 120, by 1800, 370.

The Minets in Dover established their own bank. So too did the Cobbs, brewers of Margate.

Jacob Cazeneuve Troy was a partner in the Rochester, Chatham and Strood Bank. The bank opened for business 'at Mr Gillman's house' in Rochester High Street on 21 September 1789. The partners were Messrs David Day, Thomas Hulkes, Jacob Cazeneuve Troy, John Sabb and William Gillman.

The bank issued its own notes, which could be redeemed at its own offices in Rochester, or at a banker at 50 Cornhill in the City of London.

As well as facilitating investment in building, industry and so on, Chatham probably needed a bank to provide services to the transient population of Army and Navy personnel wanting access to their money, or perhaps to deposit prize money.

Most provincial banks were small, with capital of no more than £10,000. There was no such thing as limited liability. Bankers risked their entire personal wealth if they had insufficient funds if all their depositors wanted to withdraw their money at the same time.

On 30 April 1793, the Kentish Gazette reported that on 24 April at the Bull Inn, Rochester:

At a numerous and respectable Meeting of the principal creditors of the Rochester, Chatham and Strood Bank, under the firm of Mess. Day, Hulkes, Troy, Sabb and Gillman... it was unanimously resolved by the persons present, on their having seen a general statement of the accounts... that the thanks of the Public were particularly due to the Firm, for their having so zealously exerted themselves to relieve the temporary inconvenience the stoppage of the Bank occasioned, and be enabled so soon to satisfy the demands of their respective claimants.

The Bank was to be open on Thursday 25th April at the house of Mr Hulkes in Strood 'for the purpose of satisfying all demands on the Firm'.

The Rochester, Chatham and Strood Bank was not the only one in trouble in 1793, due to the uncertainty caused by the outbreak of war with France in February that year. One banking historian estimates that sixteen banks failed in 1793, six of them in the second half of March. Cobbs in Margate did not stop payments, but members of the family did have to raise private loans to meet their obligations.

Another of Jacob Cazeneuve Troy's financial ventures was the tontine. On 14 February 1792 the Kentish Gazette announced the Rochester, Chatham, Brompton and Strood Tontine Association.

For the Benefit of Survivors, at the Expiration of Five Years,

By a Subscription of Sixpence a week each share, to be paid monthly or quarterly, and to be invested in Government Security, in the names of

Edward Sison, Esq.

Thomas Mitchell, Esq. and

Jacob C. Troy, Esq., Trustees

The partners in the Rochester, Chatham and Strood Bank were to be the Treasurers.

The Trustees have already purchased stock in the 5 per cent for the benefit of this Association, and books still open to receive further subscriptions.

Agents in towns around west Kent and mid Kent were accepting subscriptions.

Tontines originated in the late seventeenth century. Initially they were a means of raising revenue for the government, or money for major building projects. The Assembly Rooms in Bath, for example, were financed by means of a tontine. The Tontine Hotel in Ironbridge was, as the name suggests, funded by a tontine, for the purpose of providing accommodation for tourists coming to see the iron bridge.

Each investor or subscriber paid capital into the tontine and received an annual interest payment in return. From the subscriber's point of view, a tontine could be a form of life assurance or investment.

As each investor died, his or her share was distributed among the survivors, so the longest lived received progressively larger payments.

The subscriber could nominate another person as the beneficiary, usually a younger person, in the expectation that the younger person would live longer and thus enjoy larger payments for a longer period.

Unlike in fiction, when the last survivor died, the tontine was wound up; there was no payout of capital.

The last government organised tontine in England was in 1789. There were 3,495 nominees, 440 of whom were still alive in 1868. The last survivor died in 1887.

Government tontines ended, but local tontines, purely as means of investing money, rather than to raise money for any particular purpose, continued to be popular.

Local tontines reached their peak in Britain in the 1780s and 1790s, with many thousands of subscribers investing in schemes all over the country.

The Kentish Tontine, based in Maidstone, was advertised in August 1792.

East Kent already had the Dovor (sic) Tontine, advertised in October 1790. The treasurers were the Dover bankers Fector and Minet.

The Dover Tontine had agents all over the county, including Mr Gillman in Rochester. The Equitable and Universal Tontine Society also had agents in Chatham. In 1796 Rochester subscribers to the Royal Universal Tontine society were given notice of a new agent appointed to receive subscriptions.

There was thus no shortage of opportunities for people in Rochester or Chatham wanting to subscribe to a tontine.

The Rochester, Chatham, Brompton and Strood Tontine Association is not mentioned in the Kentish Gazette after the initial advertisement. It is not known whether it attracted enough subscriptions to be viable.

Tontines established as assurance or annuity funds generally invested in goverment stock - 'consols' - and used the interest from that investment to pay out to subscribers. Following the outbreak of war with France in 1793, the value of consols, and the return on investment, fell. On 16 September 1796, the Kentish Gazette reported that fixed term tontines which were now falling due, their seven years having expired, 'have all failed, owing to the great difference of the Stocks'.

Some of Jacob Cazeneuve Troy's financial sidelines may not have prospered, but his will showed him to have been a wealthy man.

Next: Jacob Cazeneuve Troy Part III: his Will

_____________________________

See my historical mystery fiction on Amazon Kindle here

Comments

Post a Comment